The decade-long story of the Astrazione povera group is a particularly interesting example for understanding the dynamics surrounding the world of abstract painting in the 1980s. It is especially so when considered in relation to the Roman context, which was blinded by the commercial and mass media successes of Achille Bonito Oliva’s neo-expressionist Transavanguardia. In that period, in Rome, many artistic experiences met to restore the concept of image, surpassing some sort of conceptualism. Such realities grew within a group and were the results of a critique system and market that served to facilitate social recognition of a specific artistic language, provided it was under the flag of the same expressive purpose.

Within these dynamics, and in complete contrast with the trends of the time, a unique line of abstract research found space and, from the end of the seventies and for the next ten years, it evolved into the practice of essential painting, exclusively in black and white (with some strokes of red), and which claimed the importance of the construction process that was to predate the making of the work. The artists, who gathered willing to define this new painting trend, were Gianni Asdrubali, Antonio Capaccio, Mariano Rossano and Rocco Salvia at first, later joined by Annibel Cunoldi Attems, Mimmo Grillo, Bruno Querci and Lucia Romualdi: the painters of Astrazione povera (whose Italian name recalls its essential aesthetics, meaning, literally, ‘poor abstraction’).

Beginning with practical and theoretical experimentations in their self-managed space in Sant’Agata dei Goti Street in Rome, the group’s first core path was formed through dialogue with perceptive critics and gallerists, such as Simonetta Lux, Fulvio Abbate and above all Gian Tommaso Liverani, who was the long-time owner of La Salita Art Gallery and among the first to open the doors of his gallery to these artists. However, it is Filiberto Menna’s contribution that was the most substantial. Menna (Salerno, 1926 – Rome, 1989) was a historian and a militant critic, who from 1985 took the responsibility of being the theoretical guide for the new movement that would soon take the name Astrazione povera. He promoted a series of exhibitions and publications of national appeal that not only defined the activity area of the group, but tried to include the Astrazione povera in a line of continuity with the Italian abstract tradition.

The dynamics of the group did not nullify the unique disposition of each individual work; this is well expressed in works by Asdrubali, Cunoldi and Querci, whose research spanned many topics and techniques, from works and panels of small size to large-scale paintings reminiscent of the telero, a technique typically used in Venice in the fourteenth century.

Gianni Asdrubali, for example, has explored the sign-space-colour trio since the late seventies, focusing on the relationship between action-tension of the artistic act. In Aggroblanda, a work belonging to a series with the same name created between 1983 and 1984, Asdrubali developed the themes of lack, absence, and emptiness through large black-filled areas painted with a parabolic movement, which alternate with areas where the preparation layer of white is left visible. Despite the gesture’s speed, which is a predominant characteristic of Asdrubali’s artistic practice, the lines are traced with a controlled and clear movement. Similarly controlled and clear is the movement that forms the painting Nemico (1987), the symbol of a transition period characterised by a change in the gesture’s speed and with the canvas’s space welcoming lines from an increasingly concise movement. This transition is concluded with the creation of the series of works called Eroica (1988), where the quickened gestuality of the sign speaks through “quantum” vocabulary.

Annibel Cunoldi Attems’s artwork has its foundation in drawing and especially in graphic design, since her earliest studies in the artistic field during the seventies in Paris. The many editions containing her engravings, which were created in the famous Atelier Lacourière-Frélaut, belong to her Parisian period. In the 1980s, her research moved towards an abstract line that aims for a synthesis of the sign structure, which is carried out through minimalist elements such as clear lines, crossing and overlapping with one another. A fine example of this technique is the series of engravings named Alibi (1985), where the artist uses symmetrical images and the element of positive-negative to emphasise how there are always two different sides from which to observe the very same situation. In the works Significazione, Comunicazione and Diversificazione the choice to use triangles stands out: this geometric shape, crucial in Cunoldi Attems’s production, is being used both to express and to point out the tension between elements, and to avoid that the work is delimited in the standard format of the canvas. In the eighties, the artist started working on large canvases characterised by complex abstract patterns that also acquired an architectural value, like in the monumental triptych named Vitalità, the only work of the section that differs from the strict black and white format to give space to the red-white combination, as Cunoldi Attems used red to indicate “another'' contrast.

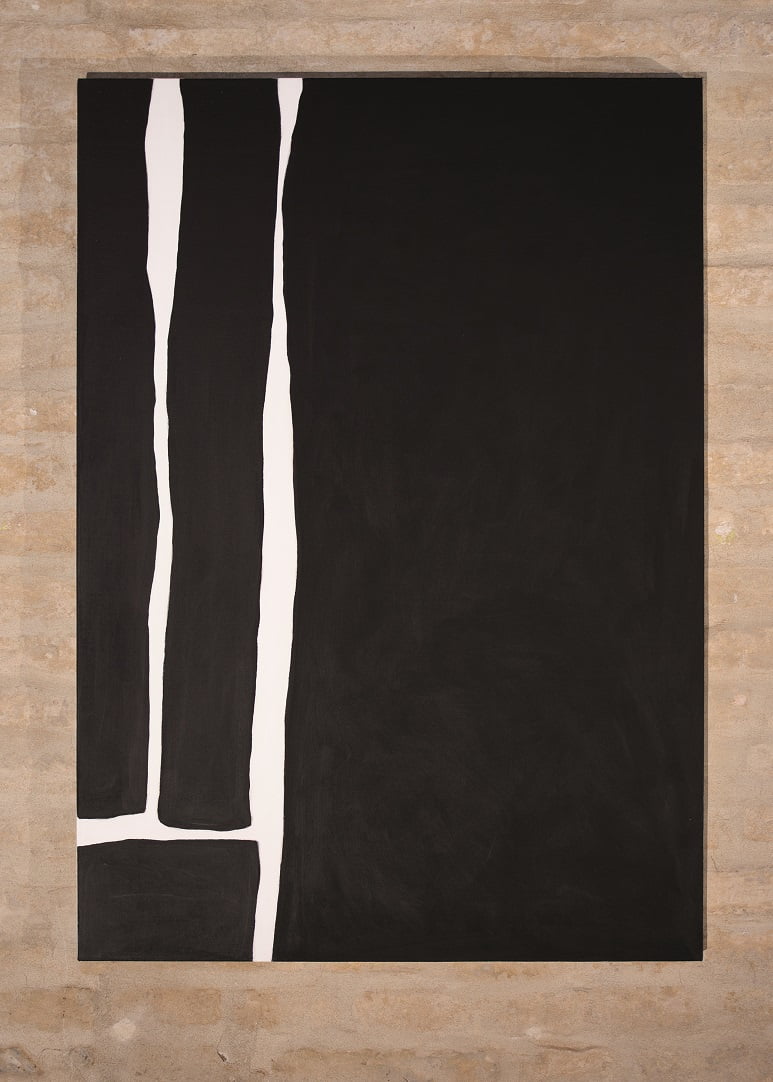

Lastly, Bruno Querci’s works show well the gradual shift from the minimalist-oriented early archaic shapes, such as Figura (1985) and Convergere (1985), to more structured works created through the overlapping of the two combinations of black-white and figure-background, clearly noticeable in the works entitled Luogo (1986) and Progetto minimo (1987). In fact, the two paintings from the mid-eighties still show a hierarchical relationship between figure and background: large black shapes prevail on the canvas surface. The shapes with their irregular contours seem to expand from the center towards the sides of the support, and the same shapes seem to detach by contrast from the light-toned ground which is left at the early stage of imprimatura. In works such as Progetto minimo and Luogo, Querci deepens the study of surface and starts to think of the ground as an active component of the composition: he does not leave it empty, but instead paints it white so as to perfectly balance the relationship with black. This leads the viewer to activate a figurative perceptive logic which alternates surface and depth due to the irregular cuts crossing the canvas in its length. The introduction of the concept of light is crucial during this phase: compared to Querci’s Impressionist period (1980-1984), when the bright component was entrusted to the use of yellow, here the artist understands that “light” is shown thanks to the interaction between the chromatic shades of black and white.