Massimo Bottecchia and Livio Schiozzi chose, within abstractionism, the path of geometric and impersonal drawing, free from any external references. In different forms, they employed the most absolute executive rigour to tackle any project with obsessive precision and formal neatness.

More than thirty years after the great retrospective of Massimo Bottecchia (1928-1980) was held in Pordenone in 1989, there haven’t been many occasions to reflect on the personality of an artist who worked independently of and parallel to the artistic movements of the second half of the twentieth century. Unlike that occasion, here it is not our goal nor our presumption to show an exhaustive overview of examples from his entire career, but merely to reintroduce a series of his works after a long period of silence: they surely testify to systematic research on topics such as colour and light, where the image is controlled by the application of rules that, from time to time, find their own way of construction.

While the kinetic art and arte programmatica groups welcomed art historian Giulio Carlo Argan’s invitation to use new technological materials, while not adhering to the industrial capitalist system and still keeping a critical and “revolutionary” attitude, Bottecchia substantially ignored it. As a matter of fact, it was not in printed and quadrionda glass, nor in drilled, punched or milled surfaces, nor in an electrical mechanism that moves the components of his works that Bottecchia found the expressive possibilities of his own artistic language, but rather in India ink and tempera used with fine and precise strokes on cardboard or wood.

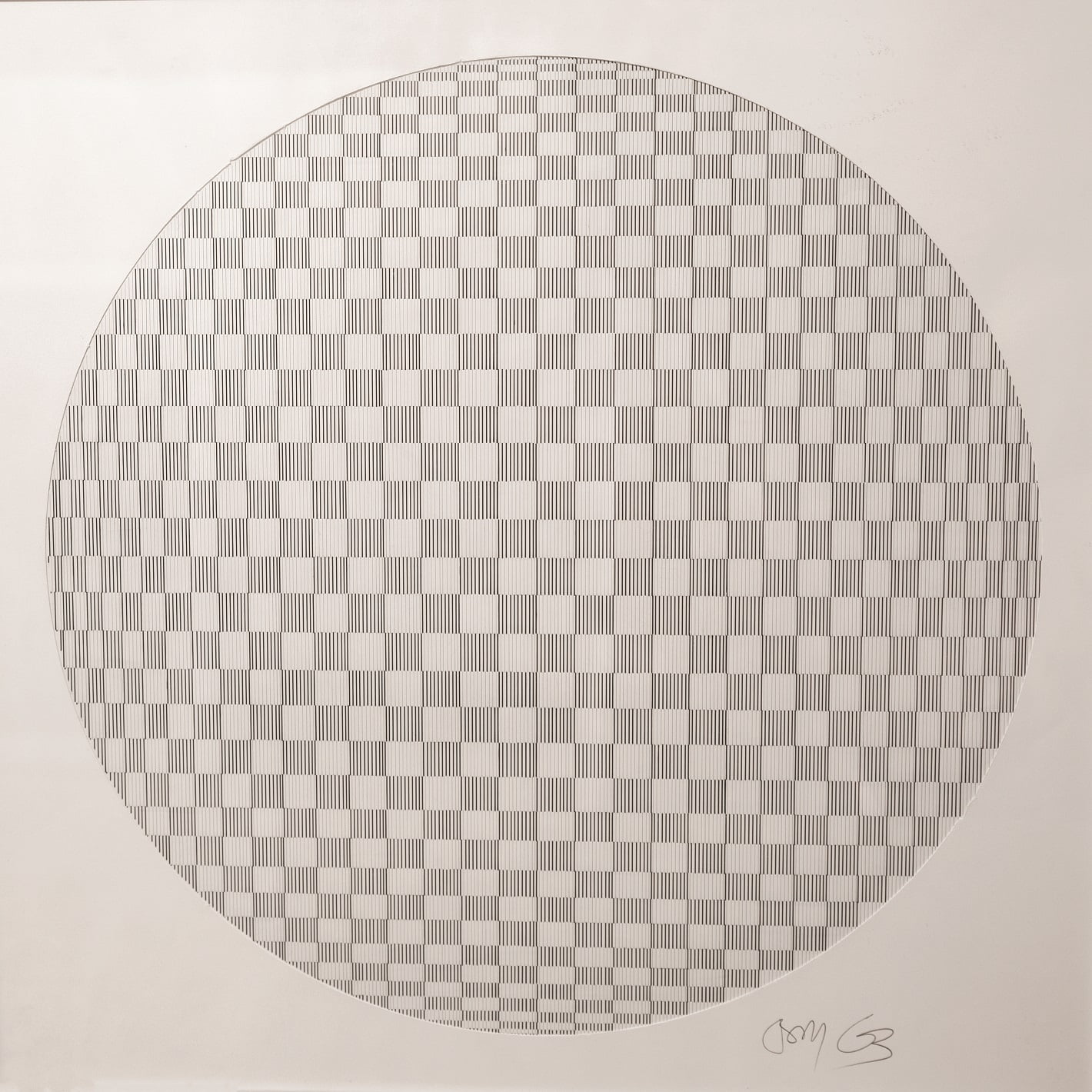

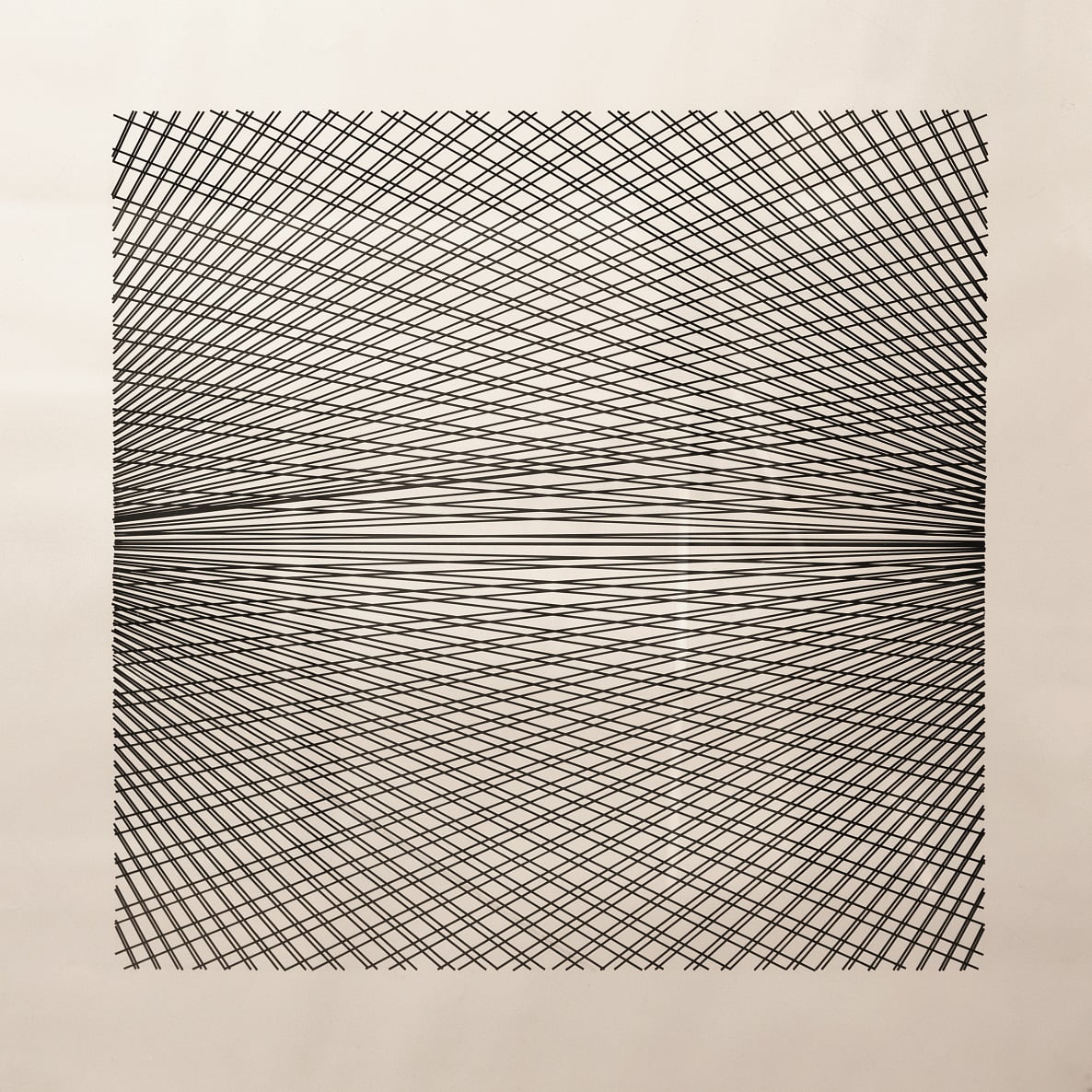

Nevertheless, in accordance with the principles of Op art, Bottecchia suggested the movement of the figures on the static and flat surface of the canvas support. A circle seems to transform into a sphere; it seems to assume a plastic consistency almost as if it were ready to shrink, to expand and emerge from the two-dimensionality of the paper. In dizzying perspectives, the sequence of the planes seems to have neither a beginning nor an end: it moves forward and looms menacingly, progressively expanding the field; a focus to infinity that disappears into an unapproachable distance, or in other cases the vanishing points become two.

An untitled work, probably created in the second half of 1970, illustrates not only the kinesthetic nature of the forms, but perhaps even more so the genesis of the artist’s work in that period. What enchants the eye is the illusion of concentric circles that expand like waves inside a circumference, while over them a spiral that creates a rotation and accentuates the dynamic push is engaged. In an exercise of extreme patience and rational control, extended and prolonged over time, Bottecchia created a thick lacework. It is impossible to count the number of coats placed one on top of the other in a twist that cannot be disentangled, in which the stratification of the sign hides the smallest white part of the paper almost completely.

The artist approached the large format only in the last three years of his work, shortly before his death in 1980; before this, his paintings had never exceeded seventy centimetres on one side. The strokes like threads of colours stitched together, the juxtaposition of complementary colours and the effects of simultaneous contrast were an opportunity to think about the heritage and to reflect on the ongoing relevance of the works of George Seurat, Gaetano Previati and Giovanni Segantini, to whom Bottecchia declared his allegiance. He would later move to refer to the works of Piero Dorazio between 1959 and the early 1970s. The different orientations of nets created by coloured lines, overlapping and mixed together, give a certain rhythm to Bottecchia’s works, which were from 1977 the result of a painting style that wanted to simulate optical perceptual vibrations.

Among the most beautiful photos that portray Livio Schiozzi (1943-2010) are undoubtedly those taken by Sergio Scabar. Thanks to their close friendship, between 1974 and 1975 the photographer joined the artist in his studio. Scabar portrayed Schiozzi at work, absorbed in thought, sitting on a chair or observed from behind, in front of a large painting. On the walls, the enlargement of an Italian poster of Sussurri e grida (‘Cries and Whispers’) by Ingmar Bergman; the poster of an exhibition of Walter Valentini with whom Schiozzi was in constant dialogue; that of an exposition in Lucerne of the Ludwig collection of American art, with Colored Maze by Frank Stella standing out. When Schiozzi did not appear in the picture, his absence was well counterbalanced by the drawing table in the centre of the scene, equipped with every professional tool. The commitment to the architectural studio of Umberto Nordio in Trieste dates back to his formative years. In Milan, where he arrived in 1966, he met Richard Sapper.

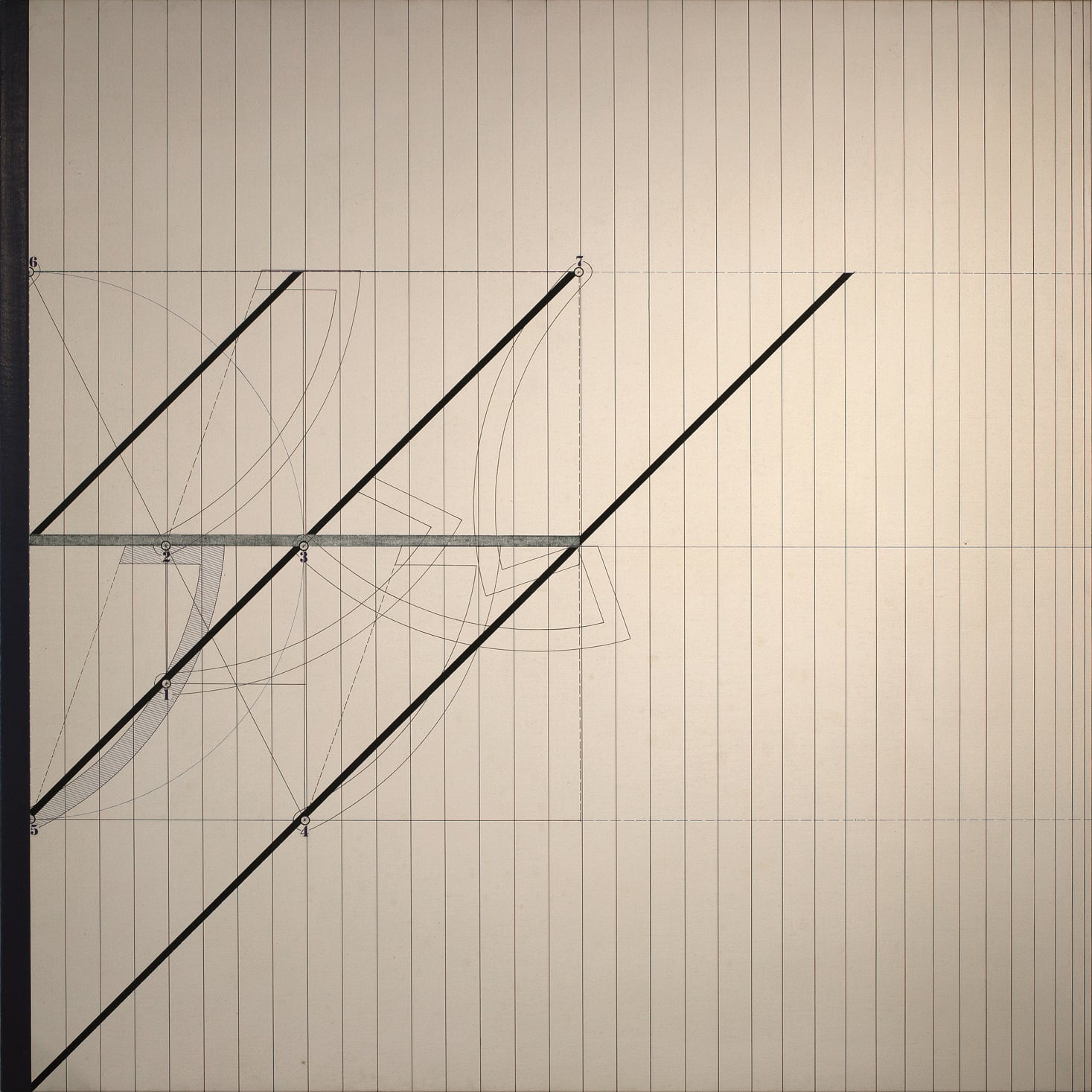

Schiozzi draws starkly impersonal lines, obtained by using India ink without any personal additions or emotional suggestions. With the aid of a French curve and a lettering guide, he created Momento di entrata diagonali I 1974, showing the movement of seven mechanical elements. Secured on pivots, the connecting rods-cranks rotate clockwise. The artist said that he had the idea for the painting after having traced some photos he had taken as a design sketch. On the transparent paper he carefully examined the image until the shapes seemed to gradually dissolve. These, almost distilled to the point of penetrating their intimate structure, were thus reduced into minimal elements. The practice described above resulted from continuous tests to confirm the formulated hypothesis to «arrive – as he declared in 1974 – to a form of objectivity of the meanings, […] to fathom apparent nonsense»[1].

Schiozzi’s works all share the same format and compositional laws that were established before their material execution. Thus, in the next development of research, roughly until 1980, Schiozzi always chose a square support and limited himself to use only horizontal, vertical, and diagonal painted backgrounds defined by a regular layout. He removed areas of the painting by erasing portions of variable sizes from the corners of the canvas. He added volumes to the surface, whose three dimensions vary and enter into relationship with the bands of colours. He then reflected on the relationship between colour and width of the coats of paint. Left exposed or painted, made vibrant by the light, the fabric reveals its texture and grain: the eye perceives what can be felt only by touch. In the long distance, Schiozzi was inspired, according to Giuseppe Marchiori, by experiences such as that of Abstraction-Création, while the artist himself identified Max Bill as a possible term of reference by explicitly quoting from him.

«I had a new idea: that is to propose an architecture of shadows». Schiozzi gave form to Boullée’s idea, as explained in the latter’s writings, with a cycle of works made between 1985 and 1988. Following the indications, he represented pyramids and cenotaphs, painted niches and doors, and built towers. We are, perhaps, there, in Babel: the city to which the “Rassegna” magazine, which the artist used to read, had dedicated an entire issue to a few years before. Are the shadows those which surrounded the ruins of Piranesi, as Pietro Cordara pointed out in commentary of the artist’s works? Those – described by Boullée – of the winter days and of a night illuminated by the moon? Or those of an “autumn afternoon”? The quick and cursive painting reveals the complexity of steps with a tonal effect. Darkness dissolves, making room for a cerulean vent and is crossed by a shaft of light. A door is left ajar.

[1] Where not stated otherwise, all translations are ours.